This post was co-authored by Jessie Johnson-Cash and based on her presentation at the USC Midwifery Education Day.

The human microbiome is rather fashionable in the world of science at the moment. The NIH Human Microbiome Project has been set up to explore correlations between the microbiome and human health and disease. To date the human microbiome as been associated with, amongst other things obesity, cancer, mental health disorders, asthma, and autism. In this post I am not going to provide a comprehensive literature review – this has already been done, and the key reviews underpinning this discussion are: Matamoros et al. (2012) ‘development of intestinal microbiota in infants and its impact on health’and Collado et al. (2012) ‘microbial ecology and host-microbiota interactions during early life stages’. Instead I am going to focus on what this means for pregnancy, birth, mothering and midwifery.

What is the human microbiome?

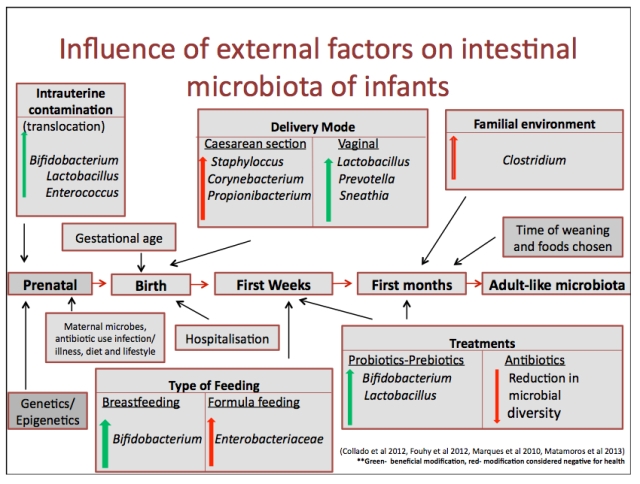

Clik here to view.

Based on a chart by Matamoro et al. 2013. Adapted and extended by Jessie Johnson-Cash.

Considerations for mothers and midwives

The following are not research based recommendations – the research is yet to be done. They are more considerations/questions arising from the developing knowledge around the human microbiome. There are quite a few health practitioners writing about gut health currently – one of my favourites is Chris Kresser because he includes references if you want to read the source of his information.

Pre-conception and Pregnancy

The commonly accepted belief that the the baby inside the uterus is sterile (whilst membranes are intact) is now being challenged. It seems that maternal gut microbiota may be able to translocate to the baby/placenta via the blood stream (Jiménez et al. 2008; Metamoros et al. 2013; Prince et al. 2014; Rautava et al. 2013; Zimmer 2013). Women’s gut microbiota change during pregnancy and this impacts on metabolism (Koren et al. 2012; Prince et al. 2014). So ideally women need to head into pregnancy with a healthy microbiome and then maintain it. Unfortunately our modern lifestyle is not very microbiome friendly, and many of us have dysbiosis (an imbalance in gut bacteria). Dysbiosis and too much of the ‘wrong’ bacteria has been linked to premature rupture of membranes and premature birth (Fortner et al. 2014; Mysorekar & Cao 2014; Prince et al. 2014).

Suggestions:

- You are what you eat… and you are the microbiota that you feed. Eat foods that nurture your microbiome: don’t eat toxins; eat fermentable fibres – starchy vegetables such as sweet potatos – they are microbiota food; eat fermented foods – kefir, sauerkraut etc. – they provide probiotics. Dietary probiotic foods may also assist with balancing vaginal microbiota (Hantoushzadeh et al. 2012; Rautava et al. 2013).

- If your gut is damaged heal it and restore the balance of microbiota. This may involve taking probiotics.

- Minimise stress. Stress messes with your gut microbiota – Chris Kresser explains how - and mother’s may pass on the effects of stress to their baby via bacteria (Bailey et al. 2011). Perhaps antenatal care should involve reassuring words and a relaxing massage rather than constant clinical testing and discussions about risk?

- Avoid antimicrobial skin products (eg. handwashes), and house cleaning products – you can watch a youtube explaining the FDAs concerns about such products.

- Avoid unnecessary pharmaceutical drugs (Bengmark 2012) especially antibiotics (Cotter et al. 2012). See Chris Kresser for more details re. antibiotics and what to do if you need to take them.

- Stop smoking (Biedermann et al. 2013).

Birth

There is a difference between the microbiome of a baby born vaginally compared to a baby born by c-section (Azad, et al. 2013; Penders et al. 2013; Prince et al. 2014). During a vaginal birth the baby is colonised by maternal vaginal and faecal bacteria. The initial bacterial colonies resemble the maternal vaginal microbiota – predominately Lactobacillus, Prevotella and Sneathia. A baby born by c-section is colonised by the bacteria in the hospital environment and maternal skin – predominately Staphylocci and C difficile. They also have significantly lower levels of Bifidobacterium and lower bacterial diversity than vaginally born babies. These differences in the microbiome ‘seeding’ may be the reason for the long-term increased risk of particular diseases for babies born by c-section.

The environment in which the baby is born also influences their initial colonisation. A study by Penders et al. (2013) found that term infants born vaginally at home and then breastfed exclusively had the most ‘beneficial’ gut microbiota. It is likely that these babies only came into contact with the microbiota of their family during the key period for ‘seeding’ the microbiome. No one has researched waterbirth and the microbiome yet. Michel Odent argues that being born through water filled with your mothers bacteria would enhance colonisation. Not sure… might it dilute the bacteria? The chance of colonisation and infection with group B streptococcus (GBS) is reduced with waterbirth (Cohain 2010; Neugeborene et al. 2007). This may be due to dilution of the GBS or additional colonisation of the baby with beneficial bacteria. Another future research topic is caul birth and the microbiome. Does a baby born in the caul miss out on colonisation via the vagina?

What we do know is that antibiotic exposure alters the microbiome in adults (see above). When a woman is given antibiotics in labour her baby also gets a dose. In 2006 a medical expert review (Ledger 2006) raised concerns about prophylactic antibiotics in labour. A study in 2011 found that antibiotics given in labour increased the incidence of late-onset serious bacterial infections in infants (Ashkenazi-Hoffnung et al. 2011). I think more research needs to be carried out considering the number of women/babies given antibiotics in labour (eg. ‘prolonged’ rupture of membranes).

Suggestions:

- A vaginal birth in the mother’s own environment is optimal for ‘seeding’ a healthy microbiome for the baby (Penders et al. 2013).

- Minimise physical contact by care providers on the mother’s vagina, perineum and the baby during birth.

- Avoid unnecessary antibiotics during labour. If antibiotics are required consider probiotics for mother and baby following birth.

- If the mother has a c-section… and I know it sounds weird but… she may want to consider swabbing her vagina and ‘wiping’ the baby with this swab. It is even more important to encourage and support breastfeeding for mothers who have had a c-section. Again, consider probiotic support.

Postnatal

After birth, colonisation of the baby by microbiota continues through contact with the environment and breastfeeding. There are significant differences in the microbiota of breastfed babies compared to formula fed babies (Azad, et al. 2013; Guaraldi & Salvatori 2012). Beneficial bacteria are directly transported to the baby’s gut by breastmilk and the oligosaccarides in breastmilk support the growth of these bacteria. The difference in the gut microbiome of a formula fed baby may underpin the health risks associated with formula feeding.

Suggestions:

- Immediately following birth, and in the first days baby should spend a lot of time naked on his/her mother’s chest.

- Avoid bathing baby for at least 24 hours after birth, and then only use plain water for at least 4 weeks (Tollin et al. 2005; RCM 2008).

- If in hospital use your own linen from home for baby.

- Minimise the handling of baby by non-family members during the first weeks – particularly skin to skin contact.

- Exclusively breastfeed. If this is not possible consider probiotic support.

- Avoid giving baby unnecessary antibiotics (Ajslev et al. 2011; Penders et al. 2013). Again, if antibiotics are required probiotics need to be considered.

Summary

The more we understand about the human microbiome the more it seems fundamental to our health. Pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding seed our microbiome and therefore have a long-term effect on health. More research is needed to explore how best to support healthy seeding and maintenance of the microbiome during this key period. I have discussed a number of considerations and suggestions arising from what we already know. I welcome any comments, discussion and further suggestions from readers.

Further reading and resources

5 ways gut bacteria affect your health

Gut feelings: the future of psychiatry may be inside your stomach

Gut bacteria might guide the workings of your minds

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.